ADHD: Hyperactive

Introduction: Attention Deficit Disorder/Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Type

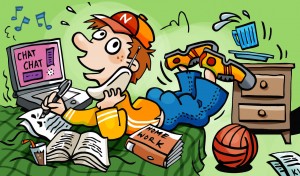

Children with Attention Deficit Disorder/Hyperactivity Disorder, Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Type are very active. These children are unable to sit still at home and in school, may be extremely fidgety or restless, may always be moving one body part or another, and may never seem to tire. Some of these children are accident-prone due to their risk-taking and impulsive behaviors, when they do not think before they act. There appear to be some differences within this type with regard to gender; girls who are described as the hyperactive-impulsive type tend to be very talkative and are often described as social butterflies, while boys are often rambunctious and aggressive.

This ADHD type is often identified in children very early on. Parents are often worried about their children being risk-takers, becoming concerned about their children’s safety. Some parents report that these children were active in the womb. Parents report that, as toddlers, these children ran before they walked, did not like to take naps, and always “got into everything” at home. As preschoolers, these children often could not sit still for a reading circle in school, could ride a two-wheeler by the age of 5, and sometimes struggled in social relationships due to their inability to regulate their activity levels and monitor the physical contact that they made with their peers.

This ADHD type is often identified in children very early on. Parents are often worried about their children being risk-takers, becoming concerned about their children’s safety. Some parents report that these children were active in the womb. Parents report that, as toddlers, these children ran before they walked, did not like to take naps, and always “got into everything” at home. As preschoolers, these children often could not sit still for a reading circle in school, could ride a two-wheeler by the age of 5, and sometimes struggled in social relationships due to their inability to regulate their activity levels and monitor the physical contact that they made with their peers.

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Hyperactive-Impulsive Type is the least diagnosed subtype of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder due to the fact that most youngsters who display these signs of hyperactivity/impulsivity also struggle with distractibility and inattention. Hyperactive-impulsive types are able to sustain their attention to tasks and do not experience any impairment at home or in school as a result of inattention. Some of these youngsters who appear to be reckless, fidgety, and talkative may also display signs of Anxiety Disorder, exhibiting a type of “nervous energy” that makes it seem like their “motors” and brains are always on.

Most commonly, youngsters who display signs of hyperactivity and impulsivity are diagnosed with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Combined Type. This diagnosis requires that a child displays a combination of inattentive and hyperactive symptoms.

Helping youngsters with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder is not as simple as medicating them. Most parents do not view medication as a first option but prefer to utilize parenting, behavioral, educational, and skill-development strategies as the primary course of action. We encourage you to look through the following list of recommendations. It is important to recognize that none of these strategies will “cure” Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder but may, when applied appropriately, reduce some of its symptoms. We caution parents to “keep it simple” by implementing a moderate number of strategies at any one time.

To learn more about the subtypes of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, see our Attention Deficit Disorder and ADHD page.

General Guidelines

1. Expect and support vigorous daily exercise. Read the book Spark by John Ratey, and learn how exercise directly changes brain chemistry that improves the ability of ADHD and learning-disabled children to learn and focus.

2. Make your ADHD child go outdoors. Research suggests that the more contact ADHD children have with nature, the less difficulty they have with inattention.

3. Watch what kids eat. While research does not indicate that diet or specific foods cause ADHD, children with ADHD clearly experience behavioral effects from the food that they eat.

4. Learn as much as you can about ADHD so that you can know when to advocate for your children and when to hold them responsible.

5. Learn to structure your children’s environment so as to minimize the distress that they experience as a result of their attention problems.

6. Be prepared. Always have a “bag of tricks” available to keep your child focused on an activity. This strategy can prevent problems across many settings.

7. Use what works. While many parents are opposed to letting their children play video games or watch television, these activities sometimes provide you with the opportunity to accomplish what you need to do and also keep your child happy. Parents can choose appropriately so that children are more likely to play video games or watch television that might improve their thinking and problem-solving skills. It is important to continue to set limits on these and other activities, but parents should not feel guilty about using them to help themselves and their children.

8. Recognize where your child’s ADHD helps, as well as hampers, him or her. For many children, ADHD is a “deficit” in the classroom but may be in an asset in other areas of their lives, including interpersonal situations, athletics, hands-on interests, and tasks that require a great deal of energy and enthusiasm. The more children can engage in activities for which their ADHD serves as a strength, the more likely they are to develop a positive sense of self-worth.

Parenting Strategies

1. Love your children by touching, hugging, tickling, and wrestling with them. Kids need a lot of physical contact.

2. Involve children in establishing rules and regulations, schedules, and family activities.

3. Tell your children when they misbehave, and explain how you feel about their behavior. Then, have them propose other more acceptable ways of behaving.

4. Help your children correct their errors and mistakes by showing or demonstrating what they should do. Don’t nag!

5. Give your children an allowance as early as possible; then, help them to plan how to spend within its limit.

6. Model and teach organizational skills. Even if you yourself are not particularly organized, be aware of many ADHD children’s need to learn such skills for home and school.

7. Actively teach planning skills. Vocalize out loud how you plan your day or the strategies that you use to accomplish a series of tasks. Encourage children to stop and plan before they act.

8. Keep children busy while in the car. ADHD Hyperactive-Impulsive children who have siblings tend to cause trouble on both short and long trips because they are easily bored. This situation is a great opportunity for ADHD Hyperactive-Impulsive children to use a hand-held video game or cell phone. Listening to music or playing selected card games are also important activities to have in your “tool box.”

9. Because many ADHD children experience a perpetual spiral of discouragement with regard to their schoolwork, they should be given praise for minor accomplishments and even good efforts that end in failure.

10. Take children to libraries, and encourage them to select and check out books of interest. Have them share their books with you. Provide stimulating books and reading material around the house. Serve as a model for children by reading and discussing material that is of personal interest to you. Share with them some of the things you are reading and doing.

11. Insist that children cooperate socially by playing, helping, and serving others in the family and the community.

12. Attend to physical factors. Research shows that a good diet and exercise improve mental performance.

13. When all is said and done, you cannot take care of your child unless you take care of yourself. Don’t bash yourself for not being a perfect parent.

Reducing Impulsivity

1. Teach methods for momentary reflection. For example, teach children to count to three before answering a question or to keep their hands in their pockets while waiting in line at school.

2. Play games at home that encourage waiting and taking turns. Find a board game or video game during which you need to alternate turns so as to help children learn to delay their activity.

3. Encourage children to ask adults if they can get up and move. This process helps them to recognize their need for movement and to reduce inappropriate or oppositional behavior.

4. Model self-control. Talk out loud about how you might wait to eat dessert until after you finish dinner or finish washing the dishes before sitting down to watch television.

5. Keep children running. The more active children are, the less likely they are to engage in inappropriately-impulsive behavior.

6. Provide routines. The more children practice a ritual at home, such as the steps one takes before going to bed, the less likely children are to engage in impulsive and inappropriate behavior.

Getting Going and Slowing Down

1. Develop a wake-up plan with the child, involving a “pre-wake-up” that employs the help of a parent or a high-tech alarm clock.

2. Use pictures, lists, or a digital picture frame to display morning routines and rituals.

3. Teach or develop a signal that instructs the child to wake up.

4. Prior to starting a task, get the child to preview what he/she will need to do in order to complete it.

5. Provide a “start” so that the child can get going, such as helping him/her begin to pick clothes up off the floor to beging cleaning his/her room; assist the child in developing an ongoing plan for the completion of the task.

6. Use verbal and visual cues to get started.

7. Alert the child to the moment when a task is starting and then have him/her report when it is finished.

8. Have the child develop a plan for starting a task and then cue him/her as to what to do. For example, if he/she chooses to watch a cartoon and then do his/her homework, then, when the cartoon ends, provide him/her a cue to get started on homework.

9. Tell the child how long he/she needs to concentrate; provide him/her with cues for beginning and end.

10. Do not force sleep. Instead, have the child stay in his/her room to read or listen to music, or provide a white noise, such as a fan, in order to help with sleep.

11. Stimulant medications may help children who just cannot get moving in the morning to become more alert. Talk to your physician. Some doctors recommend waking children up 15 minutes early, giving them their medication, and then letting them lie in bed for 15-20 minutes before getting them going.

Behavioral Management

1. ADHD children quickly habituate to rewards. It may be necessary to change the rewards regularly.

2. Parents can benefit from ongoing training and support through the use of behavioral management techniques with ADHD children. Often, parents need support in maintaining these strategies.

3. Create positive alternative choices based on your child’s purposes and encourage him/her to make a choice. If you want your child to finish a project, say, “Would you like ten minutes or fifteen to finish your project?”

4. Give an ADHD child lots of direct warnings about upcoming transitions. The feeling of being lost, out of control, anxious, and overwhelmed by stimulation can come when the ADHD child is required to pull his/her focus from one activity to another. These moments of transition must be managed carefully.

5. Parents need to learn to be able to attend to a child’s compliance and to reward his/her compliance.

6. An at-home token economy or reward system may need to be established for some difficult children.

7. Parents need to give one direction at a time to their children, since multiple directions at once are very difficult for ADHD children to manage.

Parent Education

1. Knowledge and understanding of the symptoms of ADHD are often helpful for parents. Websites, books, parenting classes, and family therapy will help parents manage a child with attentional difficulties.

2. It is also important for parents to understand the causes of oppositional defiant behavior, since many children with attentional problems may demonstrate such behavior.

3. Issues such as a child’s temperament and disabilities need to be understood.

4. Parents of ADHD children need to be fully educated in the use of time-out procedures and the methods of employing these strategies both at home and in public.

Nurturing Your Child’s Strengths

1. Look for and encourage children’s strengths, interests, and abilities. Help them to use these strong points to compensate for their limitations or any disabilities they may have.

2. Recognize what interests and engages your children. “Nudge” them to pursue these interests as they get older. For example, an ADHD child who loves to be outdoors should be steered toward learning about nature, anthropology, archaeology, landscaping, conservation, environmental engineering, or other outdoor professional fields.

3. Help your children see the strengths in their ADHD profile, such as their ability to focus on things of great interest to them or their high energy level. Help them to be optimistic about their future. Describe a number of other very successful people who have reportedly had ADHD, such as Michael Jordan, Justin Timberlake, Will Smith, Adam Levine, and Michael Phelps.

4. Inattentive children should be encouraged to engage in a variety of physical, social, and artistic activities and should be assured that perfection is not the standard by which they are measured. These children must understand that trying a new activity is more important than doing it perfectly.

Homework

1. Encourage short, frequent breaks for your child to get up and move. During these breaks, do not let your child watch television or play video games. Instead, encourage him/her to do something physical.

2. Before starting his/her homework, give your child some “running around” time during which he/she is very physically active. A short rest period with a healthy snack and a glass of milk or juice will foster homework completion.

3. Use a timer while your child studies, setting it for 10 to 15 minutes. Increase the amount of time as your child masters this amount.

4. Use music during your child’s study time. Try it out, and see what works. Usually, instrumental music is best.

5. Search for ways to reduce confrontations around homework. See if you can find a place, time, or setting that works “most of the time” for your child (perhaps use a diary to determine the best times). Remember, most homework is not fun, and you may want to integrate opportunities for rewarding activities after homework is completed.

6. If your child works hard at doing his/her homework but does it very slowly, then it may be worthwhile to talk to his/her teacher about reducing the workload. Kids need time to have fun, run around, and just relax.

7. Use self-monitoring logs for progress on long-term projects that are done jointly by you and your child.

8. Change work sites and take creative breaks (for example, move from the kitchen table to other rooms). Breaks should be brief and not overly engaging (for example, getting up to have a small snack rather than sitting down to watch television).

Medication

1. Do your research. Parents are strongly encouraged to fully educate themselves about the various types of available medications, their effectiveness, and their potential side effects.

2. Consult with a pediatrician to discuss whether or not medication is appropriate for your child.

3. Talk with friends or relatives who have experience medicating their children for attention problems.

4. Consider implementing behavioral and school-based strategies prior to the use of medication. Research indicates that there is greater overall success with ADHD children when non-medical interventions are the first line of approach and medication follows.

5. Start your child on a medication when you can observe him/her throughout the entire day. It is strongly recommended that you start your child on a medication over a weekend or school vacation, when one or both parents is able to observe the child’s behavior throughout the course of an entire day and evening.

6. Learn about the side effects of medication. There are a number of simple strategies to minimize concerns such as disturbances in sleeping, eating, and mood.

7. Children who may report some loss of appetite, particularly at lunchtime, can often compensate by eating a very healthy breakfast and having healthy snacks available to them in the evening, when their appetite increases.

8. Children who experience difficulties in falling asleep as a side effect of their medication may simply need a slightly later bedtime. They can be encouraged to engage in a relaxing activity, such as reading, drawing, or listening to quiet music, prior to going to sleep.

9. Children who have slight “rebound effects,” becoming moody while the medication is wearing off, may benefit from quiet time, an opportunity to watch a movie or television show or engage in another non-stressful activity during this period of the day. These rebound effects frequently occur in the mid to late afternoon.

10. Many children on medication are more efficient at doing their homework directly after school, since the medication may still be assisting them in their focusing capacities. Give your child a short break, a snack, and try to help them see how they are more efficient at getting their homework done when the medication is still being helpful.

11. If you choose to try medication, be patient! Don’t give up if the medication doesn’t seem to work or side effects make matters worse. Many children will need to try a few different medications and dosages in order to find what works best. Experienced physicians will hear your concerns and make appropriate medication changes for your child. With proper medication management, your child will reap the benefits of improved social, emotional, and behavioral development.

Recommended Websites

LearningWorks for Kids: The best website for learning how to use digital technologies to help your child with ADHD.

ADHD Shared Focus: An excellent website about ADHD with materials for parents and caregivers.

National Institute of Mental Health: The National Institute of Mental Health website offers extensive information that addresses a number of questions parents and teachers might have about ADHD.

CHADD: A large ADHD organization that has many great resources.

ID Online: A site that provides basic information about ADHD, its common treatments, legal rights, and useful intervention ideas for teachers and parents.

Help 4 ADHD: The National Resource Center for ADHD website, established through U.S. Center for Disease Control [CDC], answers FAQs, provides links to reliable websites, and provides opportunities to ask questions of specialists.

Mayo Clinic: Mayo Clinic provides a good overall description of ADHD symptoms.

Kids Health: A website for teens with ADHD that includes a list of strategies for teens to employ in their own lives as well as books that they may be interested in reading.

Keep Kids Healthy: A website that provides reliable information about medication for ADHD.

WebMD: Another site from which to learn about medication for ADHD.

Selected Books on ADHD for Parents

Barkley, Russell A. Taking Charge of ADHD: The Complete, Authoritative Guide for Parents. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2000. A comprehensive guide by the leading expert on ADHD.

Honos-Webb, Lara. The Gift of ADHD: How to Transform Your Child’s Problems into Strengths. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc., 2005. Suggests that many of the traits that label kids with ADHD may be an expression of deeper gifts and offers new positive techniques for dealing with ADHD.

Ingersoll, Barbara. Daredevils and Daydreamers. New York, NY: Broadway Books, 2003. A well-written update of Your Hyperactive Child. Readable, informative, and detailed.

Iseman, Jacqueline S., Sue Jeweler, and Stephan M. Silverman. School Success for Kids with ADHD. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press, 2009. Strategies to help your ADHD child at school.

Monastra, Vincent J. Parenting Children with ADHD: 10 Lessons that Medicine Cannot Teach (APA Lifetools). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2004. Explains the causes of ADHD and how nutrition, medication, and certain therapeutic procedures can improve attention, concentration, and behavioral control. Includes a plan for parents and ways to work with children’s schools.

Parker, Harvey C. Problem Solver Guide for Students with ADHD. North Branch, MN: Specialty Press, 2001. Ideas for study habits, socialization, and written language skills.

Ratey, John J., M.D. with Eric Hagerman. Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2008. Great book describing how exercise improves attention, learning, and stress management.

Rief, Sandra F. How To Reach and Teach Children with ADD/ADHD: Practical Techniques, Strategies, and Interventions.San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2005. Includes real-life case studies, interviews, student intervention plans, and strategies for enhancing classroom performance.

Selected Books on ADHD for Children and Teens

Galvin, Matthew R. Otto Learns about His Medicine: A Story about Medication for Children with ADHD. Washington, DC: Magination Press, 2001. This book about a car helps explain to children why they should take their medication to feel better. Ages 4-8.

Kraus, Jeanne. Annie’s Plan: Taking Charge of Schoolwork and Homework. Washington, DC: Magination Press, 2006. Presents a 10-Point Schoolwork Plan and a 10-Point Homework Plan that can help readers master organizational and study skills.

Nadeau, Kathleen G. and Ellen B. Dixon. Learning to Slow Down & Pay Attention: A Book for Kids about ADHD.Washington, DC: Magination Press, 2004. Suggestions for and challenges encountered in ADHD. Ages 6-11.

Petersen, Christine. Does Everyone Have ADHD? A Teen’s Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. London: Franklin Watts, 2007. A guide designed for teens to understand ADHD and how to treat it. For teens.

Quinn, Patricia O. and Judith M. Stern (Eds.). Putting on the Brakes, Second Edition: Understanding or Taking Control of Your ADD or ADHD. Washington, DC: Magination Press, 2008. A collection of articles, activities, and puzzles for children with ADD. Ages 8-13.